#4: Why did Indonesia finally join the BRICS? (Part 1)

Under former President Jokowi, Indonesia was reluctant to join BRICS, but the current President Prabowo quickly changed this position.

Thanks for reading Indonesia in English! This is the fourth edition. Welcome ☕️

If you enjoy reading this newsletter, I would appreciate it if you could leave a comment, like this post, restack on Substack, or share with friends. All of these actions help grow the reach of this newsletter and help me keep writing.

This post is free to read. But if you enjoy reading and would like to support my work, you can buy me a coffee with the link below or by scanning the QR code.

In today’s edition, I’ll take a look at the BRICS grouping of nations.

This is a two-part series.

Part 1 will explore what the BRICS is all about. And why did Indonesia, under the Jokowi government decline to join the BRICS?

Part 2 will explore why Indonesia finally decided to join the BRICS, and the role the BRICS may play in shaping Indonesia’s future.

If this topic is something you aren’t familiar with, then don’t worry. I’m going to break it down, walk through the details and try to understand the key implications. Essentially, this is a post about Indonesia’s place in the world.

Understanding the BRICS

The term BRICS goes back to 2001. Jim O’Neill, or give him his proper title, Lord O’Neill of Gatley, was the Head of Research at Goldman Sachs and in 2001 wrote a paper titled Building Better Global Economic BRICs. At the time, the term BRICs was used in the paper to illustrate the fact that “In 2001 and 2002, real GDP growth in large emerging market economies will exceed that of the G7”. The BRICs acronym was used to signify Brazil, Russia, India and China - all fast-growing economies that were said to have strong long-term growth potential.

The BRICs were contrasted with the traditional Western grouping known as the G7. In Lord O’Neill’s paper, this contrast between the BRICs and the G7 showed that the tide was turning, that economic power was beginning to shift from West to East, a theme which is likely to be a large part of the story of the 21st century.

G7 Countries: UK, USA, Germany, France, Japan, Italy

BRICs: Brazil, Russia, India and China

BRICS: Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa

In 2010, South Africa was added to the BRICs. From now on, the S is capitalised to show that, while the pronunciation remains the same, the S now stands for South Africa. Even though South Africa’s economy is much smaller than that of the other four members, it has a strong industrial base and is the core centre for banking and finance in Africa. The other BRICS nations wanted to bring an African nation into the grouping to represent the wider non-Western and non-G7 world.

The first actual meeting of the BRICS was in Sanya, China, in 2011—although the countries had met without South Africa a couple of years earlier in Russia. It’s possible that such a grouping may have emerged in any case, but Jim O’Neill’s categorisation of the BRIC economies shone a spotlight on these nations. In the 2000s, the BRICs became a hot topic in the investing community, often being seen as a synonym for emerging market economies in general.

Yet, outside of just being an investment categorisation, it made sense for non-Western BRIC nations to consider how they could cooperate with each other more broadly. Especially as the impact of the 2007-2008 Global Financial Crisis lingered (caused by issues in the financial markets of the US and Europe), nations asked themselves if the financial system that was in place was working in their best interests.

Slow and steady in the 2010s

In the 2010s, the BRICS held annual summits. From New Delhi in 2012 to Johannesburg in 2018, each of the five member countries took turns hosting the yearly get-together. They discussed world events and areas of cooperation.

Many of these meetings in the 2010s provided the usual output. Statements affirmed solitary between BRICS members and the importance of multilateralism.

Multilateralism sounds like a good idea in itself. Of course, countries should work together, and ideally, they should do so via institutions such as the UN rather than doing things alone. However, for the BRICS nations, multilateralism has meanings beyond what many in the West would think. In the context of the BRICS, multilateralism is a call to reshape the global order:

India, the world’s most populous country and a nuclear power, isn’t a permanent member of the UN Security Council. Neither is Brazil, the world’s fifth largest country by landmass and by far South America’s biggest country.

The five permanent members of the UN Security Council are from North America, Europe, or Asia - this hasn’t changed since WW2 ended.

The post-WW2 order of today has institutions such as the UN, the World Bank, and the IMF, all headquartered in the United States.

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, these institutions seem, to many, to be very much those of a unipolar world, a world with the United States and its allies asserting institutional dominance.

BRICS countries are not seeking a bipolar world similar to that of the Cold War, with two competing power centres. Rather, they implicitly seek a multipolar world, as opposed to what they see as a Western-led unipolar world.

BRICS countries are all regional powers in their own right and consider their collective voices to be more diverse than those that shaped today’s institutions.

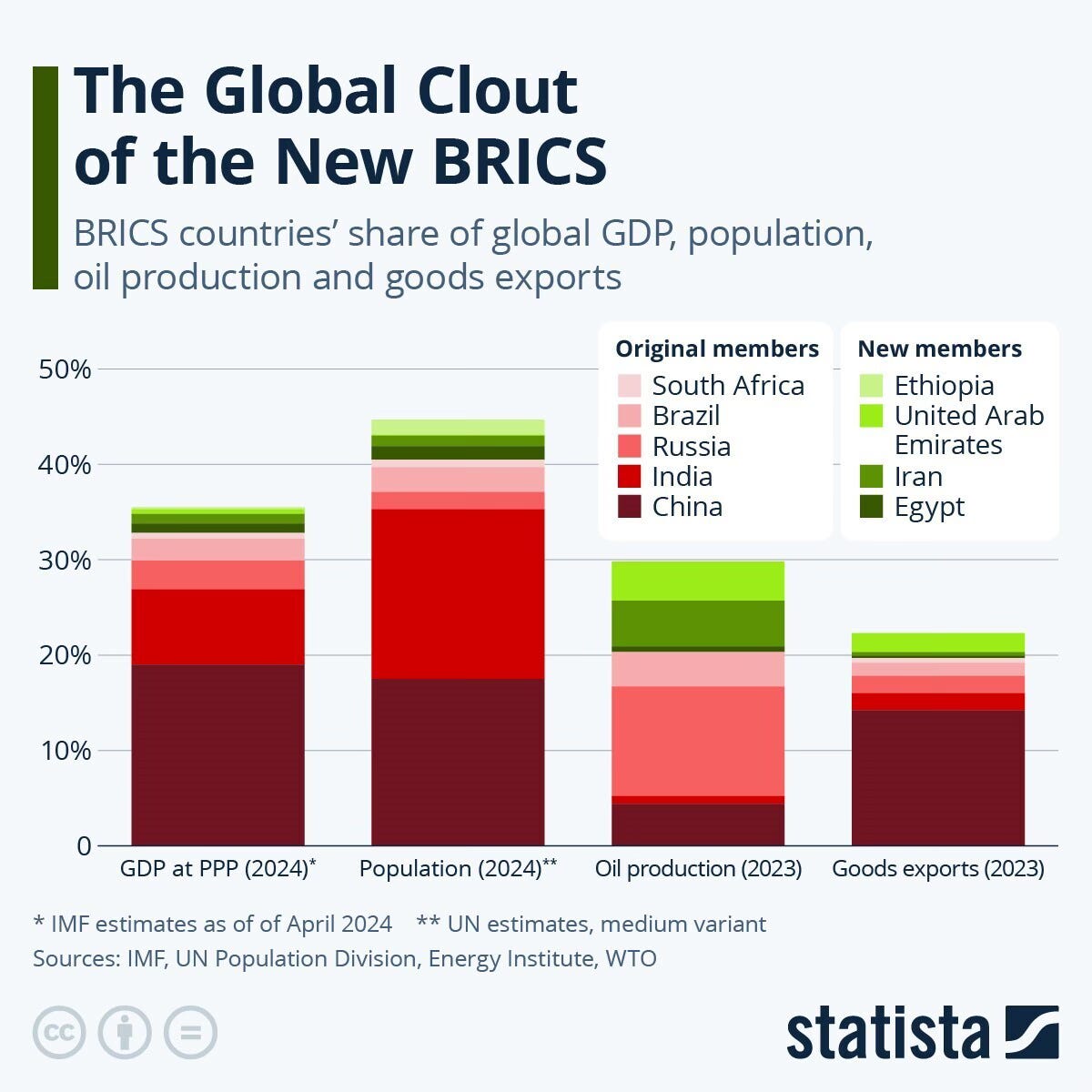

In the past twenty years, the share of global GDP that can be attributed to the BRICS doubled on a Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) basis, from 16% to 32%. Despite rising economic power and an increasing share of world GDP, the voting power of the BRICS nations in global institutions did not rise accordingly. Hence, in the 2010s, part of the BRICS agenda became crafting new institutions.

An important aspect of this process of institutional re-alignment has been the creation of the New Development Bank (NDB), which was announced following the BRICS summit in Fortaleza, Brazil, in 2014. The NDB was announced in what became known as the Fortaleza Declaration. Today, the NDB describes itself as:

A multilateral development bank established by Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa (BRICS) with the purpose of mobilising resources for infrastructure and sustainable development projects in emerging markets and developing countries (EMDCs).

The UK’s Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, at the time, described the establishment of the NDB as follows:

The centrepiece of the Summit was the formal establishment of the New Development Bank (NDB) to lend initial capital of $10bn at commercial rates for infrastructure and sustainable development projects in the BRICS and other developing countries. Each of the BRICS will subscribe $10bn within 7 years giving it a total capital base of $50bn. Each will have an equal vote on policies and disbursements. The Bank’s total authorized capital will be $100bn.

The Bank will be headquartered in Shanghai. China secured its first notable international financial institution, boosting Shanghai’s major financial centre aspirations. India holds the first 5 year rotating Presidency. South Africa got the first regional centre. Russia and Brazil have the chairs the Board of Governors, and the Board of Directors respectively.

In parallel, agreement was reached on a Contingent Reserve Arrangement (CRA) of $100bn. It aims to ‘strengthen the global financial safety net’ by providing liquidity through currency swaps to ease short term balance of payments pressures, primarily within the BRICs. China has the largest vote providing $41bn, though Russia, India and Brazil together constitute a majority.

The Contingent Reserve Arrangement (CRA) mentioned above is also notable.

In the 2007-2009 Global Financial Crisis, the US central bank, the Federal Reserve, lent almost $600bn to other central banks. The Fed became known as the global lender of last resort. These liquidity swap lines helped countries get through the financial crisis, but were limited to countries in the global North, in other words, the West, and not the BRICS. Therefore, the CRA is an attempt for BRICS nations to create their own lending facility outside the purview of the West.

How well this stands up in a mega financial crisis is yet to be tested, but it’s a clear sign of the institutional realignment ongoing.

Expansion from BRICS to BRICS+

For the first time since South Africa joined in 2010, the BRICS expanded in the 2020s.

New members who joined in January 2024:

Egypt

Ethiopia

Iran

United Arab Emirates

New members who joined in January 2025:

Indonesia

With new countries joining the organisation, the original acronym now makes less sense. Since 2024, the term BRICS+ or BRICS Plus has often been used to indicate the new larger grouping, yet officially, BRICS continues to be the organisational name.

A few months ago I was surprised to learn Indonesia was planning on joining the BRICS as Indonesia’s place in the world, had since independence been one of non-alignment. Yet Indonesia did indeed join the BRICS in January of this year.

A history of non-alignment

The policy of non-alignment was voiced by Vice President Mohammad Hatta back in 1948 in a speech titled “mendajung antara dua karang”, often translated into English as "rowing between two reefs". Hatta’s speech reflected the fact that Indonesia wanted to steer a middle ground between the US and the Soviet Union in the Cold War that was beginning to take shape at the end of the 1940s.

Then came the Bandung conference of 1955. (Bandung is one of Indonesia’s biggest cities.) Officially known as the Asia Africa Summit (Konferensi Asia–Afrika), the conference was a hugely significant meeting which brought together leaders from Asia and Africa, many of whom had recently won independence from Western nations.

Alongside the Indonesian President Sukarno were Nehru of India and Nasser of Egypt, to name just a couple of the leaders who flew to Indonesia for the conference and to lay the groundwork for what later became known as the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM). Indonesia remained non-aligned in the subsequent decades, shunning formal military alliances yet playing a central role in ASEAN (the Southeast Asia regional grouping), and actively participating in the UN and the G20.

Indonesia hosted the G20 leaders’ summit in 2022, and Chatham House reported in a post titled Indonesia shows the value of non-aligned leadership:

Indonesia is a valuable international partner because it takes its own positions on global affairs, not because it is always like-minded. On some important questions, such as the response to human rights abuses in Xinjiang and Russia’s position on the UN Human Rights Council, Indonesia did not side with liberal democracies, because it prioritizes the protection of sovereignty and resistance to perceived external interference.

On other critical questions, such as the UN General Assembly vote to condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Indonesia voted with the G7 in defence of the selfsame concept of sovereignty.Under President Joko Widodo, better known as Jokowi, Indonesia’s President from 2014 to 2024, Indonesia did not join the BRICS. Indonesia had been trying to work out it’s own path in the past years, with some rumours that Indonesia

Western officials must understand that Indonesians do not see the world in the same black and white lens that they do, assessing partner countries based on their political system and international reputation. While Indonesians are proud of their own democracy, they do not measure others by a democratic yardstick.

This analysis, from a major foreign policy think tank, offers fascinating insights into how Indonesia fits into the world. The country has steered its own path since independence, and has ensured that it’s interests are represented in its own unique way without relying on other alliances too much.

My theory is that reluctance to join the BRICS was partly due to Jokowi’s leadership style, which sought to continue Indonesia’s historic non-alignment. Jokowi has been lauded for building consensus at home and abroad, building broad coalitions within the decision-making apparatus, and offering more autonomy to regional leaders compared to his predecessors (although much more could be done here). His style was to make gradual income change, and joining the BRICS at the end of his tenure, was a step too far.

Other theories have been proposed why Indonesia didn’t join the BRICS under Jokowi. From the theory that existing members had rejected Indonesia’s membership bid, to the theory that Foreign Minister (Retno Marsudi) and Finance Minister (Sri Mulyani) opposed the idea of BRICS membership. None of these were proven. Yet in any case change was on its way.

Jokowi left power in October 2024, and by January 2025, Indonesia had joined the BRICS under new President, Prabowo Subianto. With the new presidency came significant changes. Continuity was over, and change was the new way. In part 2 of this series, we’ll look at Prabowo’s decision to join the BRICS, and what it means for Indonesia.

In general, I’m quite critical of BRICS and not too thrilled about Indonesia joining the organization. However, given the massive changes happening in the U.S. now, it’s not surprising to see more and more countries wanting to join BRICS.